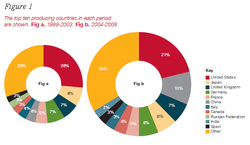

However, the measures used in the report to deduce this finding are questionable. One might ask what is the metric they are basing this finding on? Surprisingly, the metric is not a combination of factors conducive to innovation such as the one comprised by the European Innovation Scoreboard but is instead a single factor. Innovativeness is measured solely as the number of academic publication made by each country in a given year. Figure 1 is taken directly from the report and shows that in the two periods considered China has progressed from producing 4% of the world’s academic publication to 10% of the world’s academic publications. This has moved them up the ranking to second position, behind only the US.

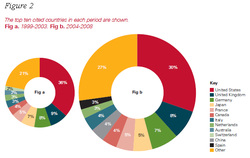

When analysing citations, which the report attributes as a possible indication of quality, the UK is ranked as the world’s number two (see Figure 2). This, the authors conclude, suggests that while China has increased the pace of its innovation, these innovations are still not of the highest quality. However, can citations really be viewed as quality? There is a propensity for individuals to cite themselves in their research, building upon what they have previously done, which would imply a self-reinforcing quality of citations. If a country produces a high number of papers, subsequently the authors will leverage off these past papers generating a higher citation count. Overall, the application of this method as a measure of the innovativeness of a country would appear deeply flawed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed