|

I have just given an interview for UTV Radio. The interview was conducted by Stephanie Grogan. It was on the current bond market crisis Italy and Spain are facing. It will be broadcast on a number of local radio stations around the country. I outlined how Italy and Spain have gone above the threshold of 6% (which is considered the maximum sustainable rate) and how these are the highest bond rates either country has faced since joining the Eurozone. My view is that, while serious, the European Commission will act to help stabilise the issue. The long term implications are likely to be changes in the structure of the Eurozone and the Stability Fund proposed.

2 Comments

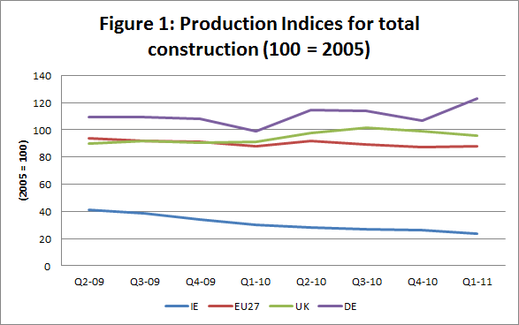

In quarter 1 of 2011 Ireland’s construction output continued to fall. Figure 1 shows Ireland’s construction output against the EU27, our closest neighbour the UK and Germany. It is clear to see that Ireland’s construction output has been hit much harder than the EU average and our neighbour the UK. Ireland’s output is only 23% of what it was in 2005 (which was not even the peak of the construction bubble). While the UK suffered a decline in construction over recent months it has increased to 2005 levels and more or less maintained these levels, with a slight fall in Q1 2011. The EU average in also holding steady at about 90% of the output of 2005. Slight seasonal fluctuations can be observed in the trend but that path is remaining fairly stable. Germany is beating the downward and constant trend, with increases in construction output. It is now producing at about 20% above 2005 levels. These figures highlight the continuing dismal state of the Irish construction industry. And worryingly, as quarter on quarter declines are still being observed, we appear to not have bottomed out yet.

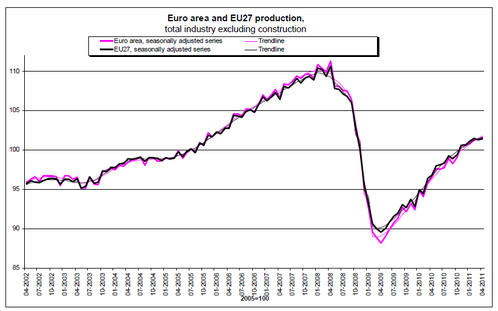

Following on from last week’s post about an increase in Ireland’s industrial output, the EU areas industrial as a whole has also risen, perhaps being a positive sign for economic recovery to some extent. Figure 1, taken from this Eurostat report, shows how, after substantial falls in 2008, industrial production is on the rise again. The graph excludes the construction industry. While figures for this industry are not available in the Eurostat report, it can be envisaged that had they been included the falloff in industrial production would have been substantially lower. The recent recovery in industrial output has allowed the EU area to rise back to a little over 2005 level output.

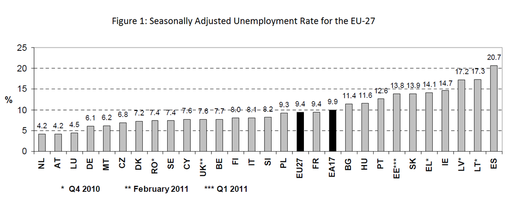

Following on from my post yesterday which showed Ireland’s unemployment rate had increased to 14.8% in May (which can be viewed here), a recent publication from Eurostat has shown that Ireland’s unemployment rate is the fourth highest in the EU. Figure 1 shows how Ireland is only behind Spain (which has an unemployment rate of 20%), Lithuania and Latvia (both of whom have unemployment rates of above 17%) in terms of the highest unemployment rate. This highlights the extent to which Ireland’s unemployment rate has climbed, from a mere 4% during the Celtic Tiger period.

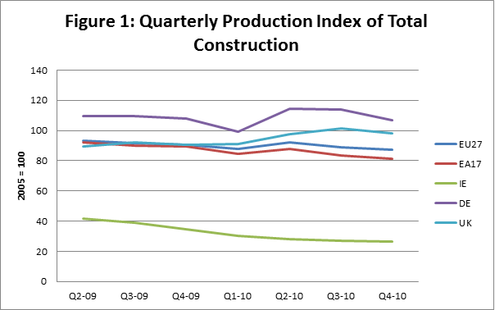

The latest figures released from Eurostat indicate that Ireland’s construction demise has been among the worst of all the EU-27 countries. Figure 1 shows this decline compared to the European average and some other selected countries. Using 2005 as the base year of 100, Ireland’s construction output has fall by 73%. This fall is far in excess of the European average which has seen a fall of only 13%. And while the Euro Area has been more adversely effected than the rest of Europe this has only fallen by 18%. Germany’s construction output is actually higher in Q4 2010 than in was in 2005 while the UK has seen improvements in construction output throughout 2010. These figures indicate that while Ireland is not the only country to be adversely effected through a collapse in the construction industry, we appear to have suffered more than most. Perhaps indicating the extent to which the construction industry in Ireland had overheated.

The BBC has produced an interactive map of some economic indicators for various EU countries. These are available here.

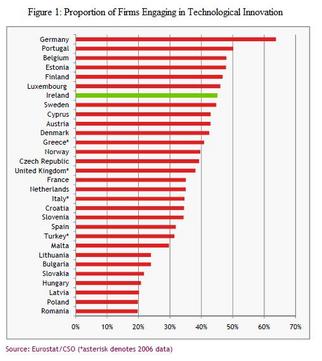

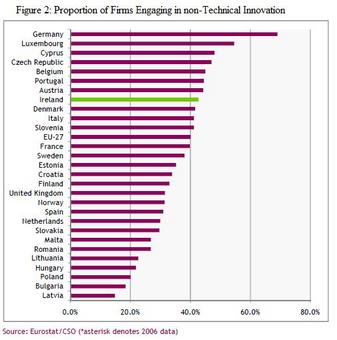

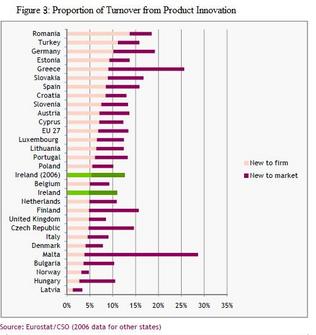

A recent report by Forfàs indicates that Ireland’s innovation performance is growing strongly. According to data from the EU wide Community Innovation Survey (CIS), displayed in Figure 1 below, Ireland is ranked 7th out of all EU member states in terms of the proportion of firms which perform technological innovation. The report defines a technological innovation as the introduction of a process or product innovation and discounts organisational or marketing innovation. Germany leads in terms of the proportion of firms engaging in technological innovation; with 63.8 percent of firms reporting that they introduced a new technological innovation during the reference period 2006-08. When considering organisational and marketing innovation (defined in teh report as non-technological innovation) it can be observed that Ireland is ranked 8th out of the EU countries. However, when analysing the effective commercialisation of these innovations Ireland’s performance falls down. Figure 2 displays the proportion of turnover derived from new to market and new to firm process innovation. It can be seen that Ireland’s position is quite low down the rankings and indeed it has even fallen since 2006. This fall may be unsurprising given that the total turnover of a substantial proportion of firms has fallen. The proportion of turnover derived from product innovations can be used to assess whether new innovations are perhaps more resistant to downward pressure on sales than traditional, older products. However, the data presented in the Forfàs report fails to provide support for this; instead suggesting innovation sales have fallen.

This suggests that Ireland may not be capitalising on the innovations it introduces. We are introducing new products, processes, organisations and marketing changes at a rate almost matching the EU leaders, however, when it comes to commercialising these innovations we are falling behind. This may suggest more of a role to play for government support in getting innovations to market and ensuring that the innovations achieve access to the desired markets to support growth. |

AuthorJustin Doran is a Lecturer in Economics, in the Department of Economics, University College Cork, Ireland. Archives

December 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed