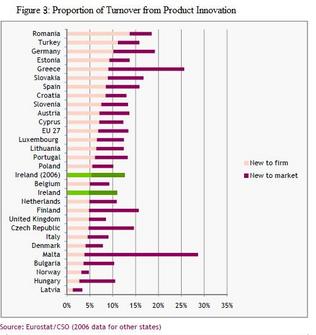

This suggests that Ireland may not be capitalising on the innovations it introduces. We are introducing new products, processes, organisations and marketing changes at a rate almost matching the EU leaders, however, when it comes to commercialising these innovations we are falling behind. This may suggest more of a role to play for government support in getting innovations to market and ensuring that the innovations achieve access to the desired markets to support growth.

|

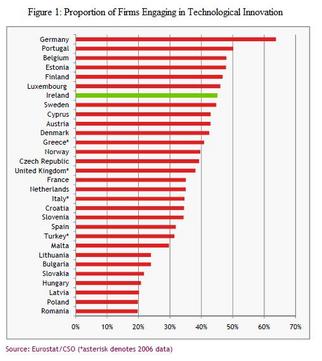

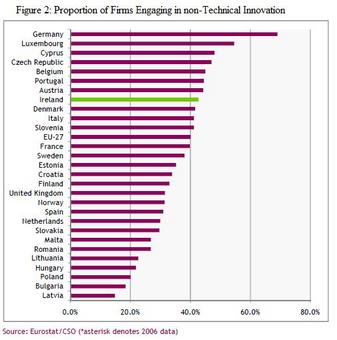

A recent report by Forfàs indicates that Ireland’s innovation performance is growing strongly. According to data from the EU wide Community Innovation Survey (CIS), displayed in Figure 1 below, Ireland is ranked 7th out of all EU member states in terms of the proportion of firms which perform technological innovation. The report defines a technological innovation as the introduction of a process or product innovation and discounts organisational or marketing innovation. Germany leads in terms of the proportion of firms engaging in technological innovation; with 63.8 percent of firms reporting that they introduced a new technological innovation during the reference period 2006-08. When considering organisational and marketing innovation (defined in teh report as non-technological innovation) it can be observed that Ireland is ranked 8th out of the EU countries. However, when analysing the effective commercialisation of these innovations Ireland’s performance falls down. Figure 2 displays the proportion of turnover derived from new to market and new to firm process innovation. It can be seen that Ireland’s position is quite low down the rankings and indeed it has even fallen since 2006. This fall may be unsurprising given that the total turnover of a substantial proportion of firms has fallen. The proportion of turnover derived from product innovations can be used to assess whether new innovations are perhaps more resistant to downward pressure on sales than traditional, older products. However, the data presented in the Forfàs report fails to provide support for this; instead suggesting innovation sales have fallen.

This suggests that Ireland may not be capitalising on the innovations it introduces. We are introducing new products, processes, organisations and marketing changes at a rate almost matching the EU leaders, however, when it comes to commercialising these innovations we are falling behind. This may suggest more of a role to play for government support in getting innovations to market and ensuring that the innovations achieve access to the desired markets to support growth.

0 Comments

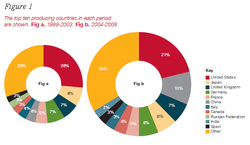

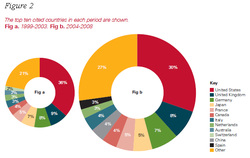

This is a copy of the slides I presented to the 3rd Business Statistics Seminar held by the CSO on the 23rd of March 2011 in Dublin Castle. The presentation focuses on sectoral differences in innovation performance. The results indicate that for two types of innovation (new to firm and new to market product innovation) the drivers of innovation vary dramatically across sectors. However, for organisational and process innovation there is no significant difference in the drivers of innovation performance. The paper points to the need for more focused innovation support from policy makers and emphasizes that a one size fits all policy is not appropriate. Doran and Jordan 23 3-2011 View more presentations from doran_justin A recent report by the Royal Society entitled Knowledge, Networks and Nations (available here) suggests that China is the second most innovative country in the world, followed by the US. It also suggests that China will overtake the US as the world’s most innovative country by 2013. If this is correct it will be viewed as a huge boost to China’s competitive position and future, long term, economic growth potential. However, the measures used in the report to deduce this finding are questionable. One might ask what is the metric they are basing this finding on? Surprisingly, the metric is not a combination of factors conducive to innovation such as the one comprised by the European Innovation Scoreboard but is instead a single factor. Innovativeness is measured solely as the number of academic publication made by each country in a given year. Figure 1 is taken directly from the report and shows that in the two periods considered China has progressed from producing 4% of the world’s academic publication to 10% of the world’s academic publications. This has moved them up the ranking to second position, behind only the US. However, are academic publications really the best gauge of a country’s innovativeness? Surely the measure of the worth of an innovation is its contribution to economics growth. But what effect does an academic publication have on economic growth? Some may have an impact should they be applicable to commercial application. However, it is easy to ask the question if it is possible to apply the discovery commercially why would it be published for all to see? Also, equal weight is allocated to each publication. What of standards? Some innovations produce higher returns to others. Similarly, different journals possess different ranking with some being more exclusive than others.

When analysing citations, which the report attributes as a possible indication of quality, the UK is ranked as the world’s number two (see Figure 2). This, the authors conclude, suggests that while China has increased the pace of its innovation, these innovations are still not of the highest quality. However, can citations really be viewed as quality? There is a propensity for individuals to cite themselves in their research, building upon what they have previously done, which would imply a self-reinforcing quality of citations. If a country produces a high number of papers, subsequently the authors will leverage off these past papers generating a higher citation count. Overall, the application of this method as a measure of the innovativeness of a country would appear deeply flawed. |

AuthorJustin Doran is a Lecturer in Economics, in the Department of Economics, University College Cork, Ireland. Archives

December 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed